fork(), calloc() and Copy-on-Write

# fork(), calloc() and Copy-on-Write

I came across

this video by Salvatore Sanfilippo explaining how Redis’s persistence model works. In his video, he mentioned copy-on-write in the context of fork(2). But since I never really understood what that meant, here I am trying to pen them down.

# Copy-on-Write (COW)

COW refers to a resource management technique which allows for an efficient copy operation. COW is based on the idea that if the memory in question is only read, everyone (processes) can simply share this same piece of memory. Hence, the copy operation is efficient, because no copying is done at all. Of course, once the memory is modified, it can no longer be shared and the copy must be performed.

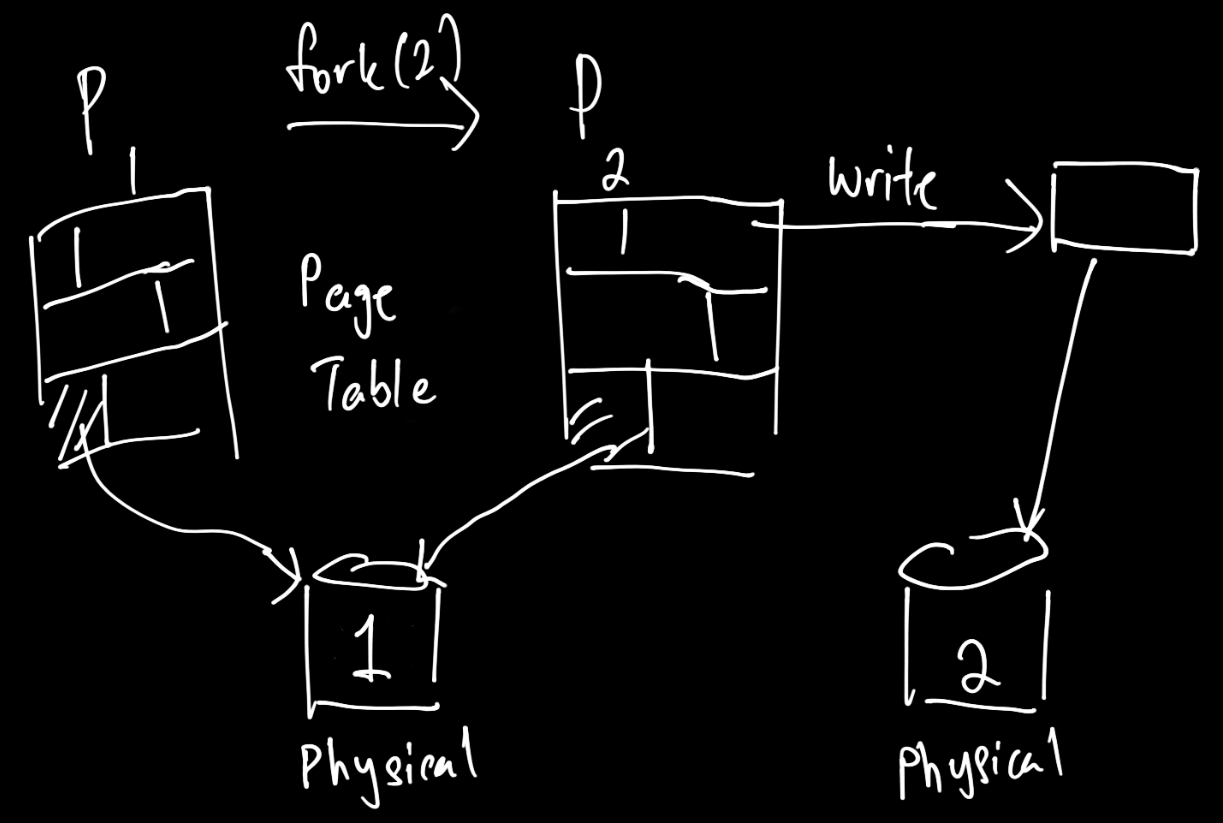

In the kernel, this is implemented in Virtual Memory, where virtual pages are backed by physical storage blocks. Processes can share the same read-only virtual memory address pointing to the same physical block up until one of them modifies the memory. When that happens, the kernel intercepts the write attempt and performs the following:

- Allocates a new physical page

- Initializes it with the shared COW data

- Update the page table with the new page and marks it as writable

- Perform the write

# fork()

What does this have to do with fork? The man page states that fork(2) creates a new process by duplicating the calling process. Duplicating. This sounds like a good place to apply COW. Consider the typical use case of fork:

| |

Here fork is used as a means to start an entirely different process (through exec), with its entirely own set of memory. If we had duplicated the entire parent process memory for this child, those operations would have been for nought. Instead, with COW, only the page table and its references are copied, shared with the parent process.

# Redis

Here is what we have discussed so far:

- COW allows processes share memory when all they need is to read from it

- When a process modifies a block of the shared memory, the kernel performs the copy, and both processes now have different references to different backing storage blocks.

- fork results in a child process which has a copy of the parent process memory, and benefits from COW since we can save on large copy operations when we typically do not need them

This is where fork() and COW come together to have interesting applications. fork() gives a child process a copy of the parent process memory at the point in time the syscall is performed. COW ensures that the parent and child process will have separate memory references when either one of them is modifies the shared memory. This means, the child process now has full read access to all the memory at that point in time, and any writes to that memory by the parent process, will not affect what the child sees. That is exactly what a snapshot needs.

Redis uses this mechanism to efficiently “copy” the in-memory keys and values stored at a point in time, and in that child process, flush this data onto the disk to create a snapshot. This comes with a few limitations. While the child process is active, any writes to the parent process will trigger COW, the real copy. If the Redis server is under heavy write load (which hits many different virtual memory pages) during this, or if the flushing to disk process takes a long time, it can result in undertaking many copy operations.

# calloc()

What brought my attention to calloc was the question “What is the difference between malloc and calloc., and when should we use either?”. From the man page, it seems that malloc() returns a pointer to uninitialized memory while calloc() sets that memory to 0.

| |

In my search for more answers, I found references to this

blog post by Georg Hager. While performing some benchmarks, they found that code which called to calloc() came up to be 7 times faster than code which simply called malloc and initialized the memory themselves.

| |

This was because calloc() did not return a reference to a fresh new memory page and filled it with zeroes. It returned a reference to a special page that was already filled with zeroes. This page had already been pre-created, and any allocations from calloc would just share this same page, up until of course when the memory is modified. So to make them the same – you guessed it, we just had to touch all that memory ourselves to trigger that sneaky COW.

| |