Exceptions

# Exceptions

A trap is a CPU generated interrupt caused by a software error or a request:

- __unhandled exceptions in a program used to transfer control back to the OS __

- user programs requesting execution of system calls which needs the OS CPU exceptions occur in various erroneous situations, for example, when accessing an invalid memory address or when dividing by zero. To react to them, we have to set up an interrupt descriptor table that provides handler functions.

On x86, there are about 20 different CPU exception types. The most important are:

- Page Fault: A page fault occurs on illegal memory accesses. For example, if the current instruction tries to read from an unmapped page or tries to write to a read-only page.

- Invalid Opcode: This exception occurs when the current instruction is invalid, for example, when we try to use new SSE instructions on an old CPU that does not support them.

- General Protection Fault: This is the exception with the broadest range of causes. It occurs on various kinds of access violations, such as trying to execute a privileged instruction in user-level code or writing reserved fields in configuration registers.

- Double Fault: When an exception occurs, the CPU tries to call the corresponding handler function. If another exception occurs while calling the exception handler, the CPU raises a double fault exception. This exception also occurs when there is no handler function registered for an exception.

- Triple Fault: If an exception occurs while the CPU tries to call the double fault handler function, it issues a fatal triple fault. We can’t catch or handle a triple fault. Most processors react by resetting themselves and rebooting the operating system.

# Interrupt Descriptor Table

The protected mode counterpart to the

interrupt vector table. Each index contains bytes needed to run handlers for different exceptions. For example, the divide by 0 handler should go in the 0 index.

# Interrupt Calling Convention

Calling conventions specify the details of a function call. For example, they specify where function parameters are placed (e.g. in registers or on the stack) and how results are returned. On x86_64 Linux, the following rules apply for C functions (specified in the System V ABI):

- the first six integer arguments are passed in registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9

- additional arguments are passed on the stack

- results are returned in rax and rdx

# Preserved and Scratch Registers

The values of preserved registers must remain unchanged across function calls. So a called function (the “callee”) is only allowed to overwrite these registers if it restores their original values before returning. Therefore, these registers are called “callee-saved”. A common pattern is to save these registers to the stack at the function’s beginning and restore them just before returning.

The values of preserved registers must remain unchanged across function calls. So a called function (the “callee”) is only allowed to overwrite these registers if it restores their original values before returning. Therefore, these registers are called “callee-saved”. A common pattern is to save these registers to the stack at the function’s beginning and restore them just before returning.

In contrast, a called function is allowed to overwrite scratch registers without restrictions. If the caller wants to preserve the value of a scratch register across a function call, it needs to backup and restore it before the function call (e.g., by pushing it to the stack). So the scratch registers are caller-saved.

# x86-interrupt convention Preserving All Registers

In contrast to function calls, exceptions can occur on any instruction. Since we don’t know when an exception occurs, we can’t backup any registers before. This means we can’t use a calling convention that relies on caller-saved registers for exception handlers. The x86-interrupt calling convention does this by backing up registers overwritten by the function on function entry.

# Interrupt Stack Frame

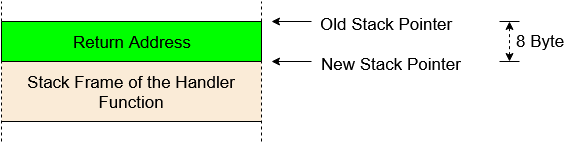

A normal function call stack frame (the return address is pushed to the stack to allow the CPU to return back to the caller):

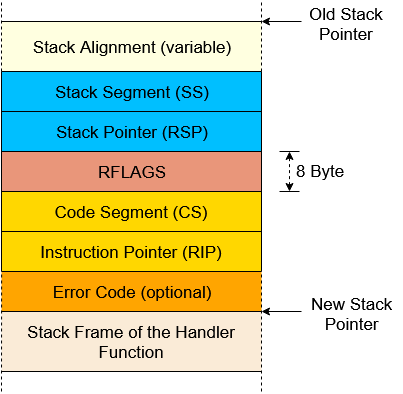

An interrupt stack frame:

An interrupt stack frame:

- Saving the old stack pointer: The CPU reads the stack pointer (

rsp) and stack segment (ss) register values and remembers them in an internal buffer. - Aligning the stack pointer: An interrupt can occur at any instruction, so the stack pointer can have any value, too. However, some CPU instructions (e.g., some SSE instructions) require that the stack pointer be aligned on a 16-byte boundary, so the CPU performs such an alignment right after the interrupt.

- Switching stacks (in some cases): A stack switch occurs when the CPU privilege level changes, for example, when a CPU exception occurs in a user-mode program. It is also possible to configure stack switches for specific interrupts using the so-called Interrupt Stack Table (described in the next post).

- Pushing the old stack pointer: The CPU pushes the

rspandssvalues from step 0 to the stack. This makes it possible to restore the original stack pointer when returning from an interrupt handler. - Pushing and updating the

RFLAGSregister: TheRFLAGSregister contains various control and status bits. On interrupt entry, the CPU changes some bits and pushes the old value. - Pushing the instruction pointer: Before jumping to the interrupt handler function, the CPU pushes the instruction pointer (

rip) and the code segment (cs). This is comparable to the return address push of a normal function call. - Pushing an error code (for some exceptions): For some specific exceptions, such as page faults, the CPU pushes an error code, which describes the cause of the exception.

- Invoking the interrupt handler: The CPU reads the address and the segment descriptor of the interrupt handler function from the corresponding field in the IDT. It then invokes this handler by loading the values into the

ripandcsregisters

# Double Faults

A double fault is a special exception that occurs when the CPU fails to invoke an exception handler. For example, it occurs when a page fault is triggered but there is no page fault handler registered in the IDT. So it’s kind of similar to catch-all blocks in programming languages with exceptions.

Only certain combinations of exceptions can trigger double faults:

| First Exception | Second Exception |

|---|---|

| Divide-by-zero, Invalid TSS, Segment Not Present, Stack-Segment Fault, General Protection Fault | Invalid TSS, Segment Not Present, Stack-Segment Fault, General Protection Fault |

| Page Fault | Page Fault, Invalid TSS, Segment Not Present, Stack-Segment Fault, General Protection Fault |

| A double fault must be handled properly, else some cases can easily transition into a triple fault causing a system reset. Kernel stack overflow is one of them. |

# Kernel Stack Overflow

What happens if our kernel overflows its stack and the guard page is hit?

- A guard page is a special memory page at the bottom of a stack that makes it possible to detect stack overflows. The page is not mapped to any physical frame, so accessing it causes a page fault instead of silently corrupting other memory. The bootloader sets up a guard page for our kernel stack, so a stack overflow causes a page fault.

- When a page fault occurs, the CPU looks up the page fault handler in the IDT and tries to push the interrupt stack frame onto the stack. However, the current stack pointer still points to the non-present guard page. Thus, a second page fault occurs, which causes a double fault (according to the above table).

- So the CPU tries to call the double fault handler now. However, on a double fault, the CPU tries to push the exception stack frame, too. The stack pointer still points to the guard page, so a third page fault occurs, which causes a triple fault and a system reboot. So our current double fault handler can’t avoid a triple fault in this case.