Memory Organisation

# Memory Organisation

# Virtual Memory

The idea behind virtual memory is to abstract away the memory addresses from the underlying physical storage device. Instead of directly accessing the storage device, a translation step is performed first. For segmentation, the translation step is to add the offset address of the active segment. Imagine a program accessing memory address 0x1234000 in a segment with an offset of 0x1111000: The address that is really accessed is 0x2345000.

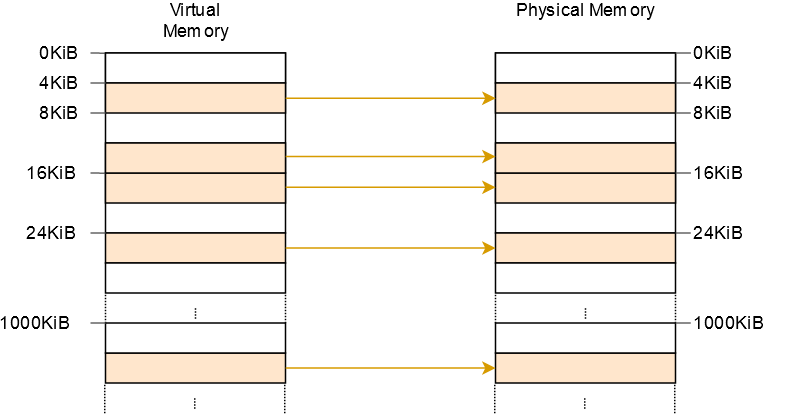

This allows both programs to run the same code and use the same virtual addresses without interfering with each other:

# Address Binding

A program needs to be loaded into memory to run. The machine code that is generated needs to be mapped to memory addresses in the system.

Possible binding stages:

Possible binding stages:

- Compile time: memory location is known a priori, generating absolute code that must be recompiled if the starting location changes

- Load time: compiler generates relocatable code and the binding is performed by the loader.

- Execution time: binding is delayed until run time and the process can be moved during its execution from one memory segment to another. Uses a logical address that is relative to a starting 0 point.

# Fragmentation

[! ] Internal Fragmentation: allocated memory may be larger than requested memory, this results in unusable memory within the partition

External Fragmentation : unusable memory between partitions

# Memory Allocation

How to assign memory to different processes?

# Contiguous allocation

Logical address space of process remains contiguous in physical memory.

# Fixed partitioning

Memory is partitioned into regions with fixed boundaries. OS decides which partition to assign a process to depending on the available partitions.

Internal fragmentation: as each partition is fixed, a process assigned to a partition might not take up the entire space of the partition, resulting in wasted unusable memory internal to the partition.

Internal fragmentation: as each partition is fixed, a process assigned to a partition might not take up the entire space of the partition, resulting in wasted unusable memory internal to the partition.

# Dynamic partitioning

Do not partition the memory. Rather, the OS allocates the exact chunk of memory which a process requires, and keeps tracks of holes or available blocks of memory.

External fragmentation: memory space between partitions (the holes) may be enough to satisfy a new request but is not contiguous and cannot be used. This can be solved by performing compaction, which shuffles memory contents to produce contiguous block of available memory.

External fragmentation: memory space between partitions (the holes) may be enough to satisfy a new request but is not contiguous and cannot be used. This can be solved by performing compaction, which shuffles memory contents to produce contiguous block of available memory.

# Dynamic Allocation Policies

# Problems

In contiguous allocation, the entire address space of process memory is kept together. This causes a big chunk of “free space” that lies between the stack and heap of a process which is wasted (internal fragmentation).

# Segmentation (Non Contiguous Allocation)

# Addressing

Segmentation Fault What if we try to refer to an illegal address? The hardware detects that the address is out of bounds, traps into the OS, likely leading to the termination of the offending process. That is called a segmentation fault.

# Problems

- External fragmentation: as processes leave the system, occupied segments become holes in the memory

- Segmentation still isn’t flexible enough to support our fully generalized, sparse address space. For example, if we have a large but sparsely-used heap all in one logical segment, the entire heap must still reside in memory in order to be accessed. In other words, if our model of how the address space is being used doesn’t exactly match how the underlying segmentation has been designed to support it, segmentation doesn’t work very well

# Paging

^b8969e

[!Idea:]

- Divide the physical memory into fixed sized frames.

- Divide logical memory of the process into pages the same size as frames.

- Use a page table to map the logical memory to physical memory.

# Fragmentation

- Eliminating external fragmentation as every available physical memory space can be utilised.

- Internal fragmentation still possible as the last page may not use up the entire frame.

# Address Translation

Split the logical address to map page to frame:

Offset necessary to locate the byte-addressable piece of physical memory.

Offset necessary to locate the byte-addressable piece of physical memory.

# Hardware Support

The page table is stored in main memory with a page table base register (PTBR) pointing to it.

# Translation Look-aside Buffers (TLB)

The page table is stored in memory and thus, to access a piece of physical memory, we require 1 memory access to the page table and 1 memory access to the actual memory. We can speed this up with a specialised cache for the page table.

# Effective access time

With TLB:

- 1 TLB access and 1 mem access on hit

- 1 TLB access and 2 mem access on miss

# Shared Pages

Reentrant or code which never changes during execution can be shared among processes by having processes used the same pages.

# Multi-level Paging

A page table can be large. Not efficient to have to fetch the entire page table for every memory LOAD/STUR instruction.

The multi-level table only allocates page-table space in proportion to the amount of address space you are using (a linear page table would require the whole thing to reside in memory to correctly perform address translation); thus it is generally compact and supports sparse address spaces.

# Paging the page table

- Final level represents the physical memory space, 12 bits is needed for byte-addressing the 4KB memory. This leaves 20 bits for indexing pages.

- Second level represents the index to the first level page: There are $2^{20}$ pages. Each page in this level is 4 bytes so as to map to the address of a 4byte page address.

- The root level represents the index to the 2nd level page: Since 1 block can store 4KB, to store information about the 4MB page table in 1 block will require $2^{20}\times4/2^{12}=2^{10}$ entries

Hence, 10 bits to access 1 out of $2^{10}$ pages which itself contains 10 bits to access 1 out of $2^{10}$ pages. Total of $2^{20}$ pages.

Trade-offs On a TLB miss, two loads from memory will be required to get the right translation information from the page table (one for the page directory, and one for the PTE itself

# Inverted Page Table

[! Idea:] Rather than each process having its own page table, we only keep a single table with 1 entry for each physical frame.

- Each entry contains the

process-idandpage-number- To find a matching entry for a logical address, we need to find the entry that has the equivalent proces_id and page_number pair

We gain in terms of memory, as we no longer have a page table size that is proportional to logical addressing space. We lose in terms of speed, as we need to search the page table rather than addressing it directly with a page index.

We gain in terms of memory, as we no longer have a page table size that is proportional to logical addressing space. We lose in terms of speed, as we need to search the page table rather than addressing it directly with a page index.

# Accessing Page Tables

Most operating systems kernels run with paging enabled. This means that memory accesses in the kernel are inherently through virtual addresses. This is good, since programs could easily circumvent memory protection and access the memory of other programs otherwise. So the only way to access some physical address is through some virtual page that is mapped to the physical frame at address.

# Identity mapping

This way, the physical addresses of page tables are also valid virtual addresses so that we can easily access the page tables of all levels

However, it clutters the virtual address space and makes it more difficult to find continuous memory regions of larger sizes i.e. fragmentation.

However, it clutters the virtual address space and makes it more difficult to find continuous memory regions of larger sizes i.e. fragmentation.

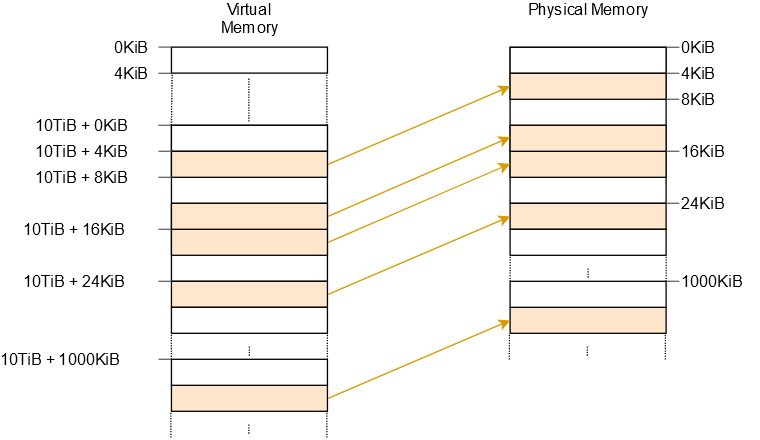

# Fixed offset mapping

We can use a separate memory region for page table mappings, for example, at 10 TiB:

However, this means we still have to create a new mapping whenever we create a new page table.

However, this means we still have to create a new mapping whenever we create a new page table.

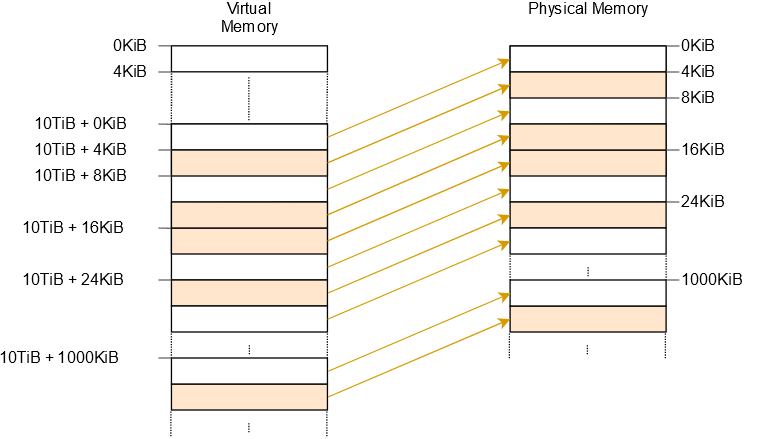

# Map the complete physical memory

This approach allows our kernel to access arbitrary physical memory, including page table frames of other address spaces. The reserved virtual memory range has the same size as before, with the difference that it no longer contains unmapped pages.

However, additional page tables are needed for storing the mapping of the physical memory. These page tables need to be stored somewhere, so they use up a part of physical memory, which can be a problem on devices with a small amount of memory.

However, additional page tables are needed for storing the mapping of the physical memory. These page tables need to be stored somewhere, so they use up a part of physical memory, which can be a problem on devices with a small amount of memory.

# Practice Problems

c. First fit lower overhead. Only moved 1 block compared to 3 blocks in best fit.

a. Fixed partitioning

b. Process memory is based on absolute addresses and is unable to be relocated for memory compaction.

a. Fixed partitioning

b. Process memory is based on absolute addresses and is unable to be relocated for memory compaction.

a. 200ns to access the page table. Another 200ns to access the memory frame. Total time: 400ns

b. $$\text{Total time}=0.75\times200+0.25\times400=250ns$$

a. 200ns to access the page table. Another 200ns to access the memory frame. Total time: 400ns

b. $$\text{Total time}=0.75\times200+0.25\times400=250ns$$

a.

To address a byte in a 1-Kbyte page will require 10 bits

Logical address: 22 bit page index, 10 bit offset

1 Gigabyte ($2^{30}$) physical memory will require, 30 bits to represent each byte address

a.

To address a byte in a 1-Kbyte page will require 10 bits

Logical address: 22 bit page index, 10 bit offset

1 Gigabyte ($2^{30}$) physical memory will require, 30 bits to represent each byte address

b.

$2^{22}$ pages.

c.

Number of entries = Number of physical frames: $2^{30}/2^{10}=2^{20}$

b.

$2^{22}$ pages.

c.

Number of entries = Number of physical frames: $2^{30}/2^{10}=2^{20}$

a.

There are 8 pages, 3 bits are required to determine the page index.

Remaining 7 bits are used for the page offset, to address the individual byte in the page.

1000011011 -> Page 100 Offset 0011011 -> Page = 4 -> Frame number 01001

Physical address: $010010011011$

b.

There are 4 segments, 2 bits required to determine segment number

Remaining 8 bits used to address the physical memory unit

1000011011 -> Segment 10 Offset 00011011 -> Segment = 2

a.

There are 8 pages, 3 bits are required to determine the page index.

Remaining 7 bits are used for the page offset, to address the individual byte in the page.

1000011011 -> Page 100 Offset 0011011 -> Page = 4 -> Frame number 01001

Physical address: $010010011011$

b.

There are 4 segments, 2 bits required to determine segment number

Remaining 8 bits used to address the physical memory unit

1000011011 -> Segment 10 Offset 00011011 -> Segment = 2

a.

Number of pages = $2^{30}/1024=2^{20}$

Size of table = $2^{20}\times4=2^{22}$

b.

$$

\begin{align}

&\text{Size of page table 1st level}=2^{22}\\ &\text{Number of pages 2nd level}=2^{22}/2^{10}=2^{12}\\ &\text{Size of 2nd level}=2^{12}\times4=2^{14}\\ &\text{Number of pages 3rd level}=2^{14}/2^{10}=2^4\\ &\text{Size of 3rd level}=2^4\times4=2^6<1024B\\ &\text{Total no. of levels}=3

\end{align}

$$

c.

3rd level holds $2^4$ pages and requires 4 bits to index

Each page table can hold $2^{10}/2^2=2^8$ entries

8 bits needed to index into the 2nd level

Each page table in the 2nd level holds $2^8$ entries

8 bits needed to index into the final level

a.

Number of pages = $2^{30}/1024=2^{20}$

Size of table = $2^{20}\times4=2^{22}$

b.

$$

\begin{align}

&\text{Size of page table 1st level}=2^{22}\\ &\text{Number of pages 2nd level}=2^{22}/2^{10}=2^{12}\\ &\text{Size of 2nd level}=2^{12}\times4=2^{14}\\ &\text{Number of pages 3rd level}=2^{14}/2^{10}=2^4\\ &\text{Size of 3rd level}=2^4\times4=2^6<1024B\\ &\text{Total no. of levels}=3

\end{align}

$$

c.

3rd level holds $2^4$ pages and requires 4 bits to index

Each page table can hold $2^{10}/2^2=2^8$ entries

8 bits needed to index into the 2nd level

Each page table in the 2nd level holds $2^8$ entries

8 bits needed to index into the final level