Representing Code

# Representing Code

# Context Free Grammars (CFG)

A formal grammar’s job is to specify which strings are valid and invalid. If we were defining a grammar for English sentences, “eggs are tasty for breakfast” would be in the grammar, but “tasty breakfast for are eggs” would probably not.

# Defining CFG

A CFG production is defined with:

- head: a name

- body: describing what it produces

- A terminal is a letter from the grammar’s alphabet. You can think of it like a literal value. In the syntactic grammar we’re defining, the terminals are individual lexemes—tokens coming from the scanner like

ifor1234.- These are called “terminals”, in the sense of an “end point” because they don’t lead to any further “moves” in the game. You simply produce that one symbol.

- A nonterminal is a named reference to another rule in the grammar. It means “play that rule and insert whatever it produces here”. In this way, the grammar composes.

- A terminal is a letter from the grammar’s alphabet. You can think of it like a literal value. In the syntactic grammar we’re defining, the terminals are individual lexemes—tokens coming from the scanner like

# Our own CFG grammar notation

Breakfast menu grammar example:

| |

Simplified with additional notation:

| |

Applied to a programming language:

| |

# Abstract Syntax Tree

A data structure to represent language grammars.

# Implementation

We can use a base class Expr to hold the different expression types:

| |

# Parsing Code

The 2 jobs of a parser:

- Given a valid sequence of tokens, produce a corresponding syntax tree.

- Given an invalid sequence of tokens, detect any errors and tell the user about their mistakes.

# Precedence and Associativity

Different expressions have different precedence and associativity rules.

The C programming language rules with precedence from top to bottom:

Applying the rules to our grammar notation:

| |

Each lower precedence expression matches internally to a higher precedence expression. For example, equality can either match an equality expression like a b, or for an expression like a >= b, it calls the matching rule for comparison.

# Adding ternary ?: operator

The ternary operator should have lowest precedence.

conditional -> equality ("?" expression ":" equality)?

# Recursive Descent Parsing

A top-down parser starting from the top or outermost grammar rule (here expression) and working its way down into the nested subexpressions before finally reaching the leaves of the syntax tree. This is in contrast with bottom-up parsers like LR that start with primary expressions and compose them into larger and larger chunks of syntax.

Translating the

grammar rules into code maps nicely into recursive function calls:

equality → comparison ( ( "!=" | "" ) comparison )* ;

is

| |

# Error Handling

# Panicking

As soon as the parser detects an error, it enters panic mode. It knows at least one token doesn’t make sense given its current state in the middle of some stack of grammar productions.

Languages like Java allows us to throw an exception.

# Synchronisation

Before it can get back to parsing, it needs to get its state and the sequence of forthcoming tokens aligned such that the next token does match the rule being parsed.

We want to discard tokens until we are at the beginning of the next statement. That boundary is usually after semicolons or before keywords like if:

| |

# Evaluating/Interpreting Expressions

To “execute” code, we will evaluate an expression and produce a value. For each kind of expression syntax we can parse—literal, operator, etc.—we need a corresponding chunk of code that knows how to evaluate that tree and produce a result.

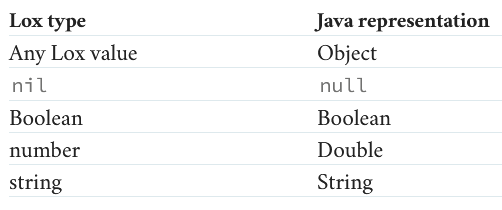

# Representing Values

Bridge the logic between the language and the underlying implementing language.

An example in Java:

# Evaluation Logic

Make use of the Visitor Pattern to apply interpreter logic on each of the expression types.

| |

# Statements

Statements do not produce a value, they need to create a side effect.

2 examples:

- An expression statement lets you place an expression where a statement is expected. They exist to evaluate expressions that have side effects.

method(); - A

printstatement evaluates an expression and displays the result to the user. Adding statements to grammar rules:

| |

# Supporting Global Variables

# Variable declaration

Variable declarations are statements but may be restricted to only be allowed in certain cases.

if (monday) var beverage = "espresso"; is weird. What is the scope of that beverage variable? Does it persist after the if statement? If so, what is its value on days other than Monday? Does the variable exist at all on those days?

Updating the grammar rules:

| |

The equivalent matching Recursive Descent Parsing code in Java:

| |

# Variable Expressions

A variable expression accesses the binding made in declaration and returns it.

| |

We update the primary expression to match an IDENTIFIER type, which corresponds to the name of the variable.

# Environments

The environment is a data structure used to store the bindings between variables and values.

You can think of it like a map where the keys are variable names and the values are the variable’s, uh, values.

You can think of it like a map where the keys are variable names and the values are the variable’s, uh, values.

Implemented in Java uses a HashMap:

| |

define(): this implementation allows for redefinitions like:

| |

This may not be what we want to allow because the user might not intend to redefine an existing variable, of which assignment should be used.

get(): the implementation decision made here is to throw a Runtime error if the identifier does not exist. If a static error is thrown instead (meaning the error is detected during parsing and not during interpreting/evaluation), we would not allow users to reference identifiers before they exist:

| |

# Interpreting Variables

We allow accessing a variable before initializing. In that case, we should return nil, the code below sets nil as the default value in the environment.

| |

Interpreting variable expressions is a simple environment access:

| |

# Assignment

An assignment is either an identifier followed by an = and an expression for the value, or an equality (and thus any other) expression.

| |

A single token lookahead recursive descent parser can’t see far enough to tell that it’s parsing an assignment until after it has gone through the left-hand side and stumbled onto the =. Why does it matter? After all, we do not care about it for operators like + anyway.

# L-value and R-value

An assignment is different because the left operand does not evaluate to any value. It only evaluates to a storage location to assign to, an l-value. Expressions like + produce only r-values.

| |

In this case, we do not want to evaluate “a” (which returns “before”).

We can parse the left side as though it is an expression. Only if we reach a =, we wrap the entire thing in a assignment expression:

| |

At the same time, if the left side is not a valid assignment target (aka not a variable in this case), we throw an error.

# Interpreting

Use an assign method which inserts into the environment only if the identifier exists, else throw a runtime error:

| |

# Scope

Lexical scope: the text of the program itself shows where a scope begins and ends, i.e. uses stuff like “{ }”, also called block scope. Dynamic scope: where you don’t know what a name refers to until you execute the code:

| |

# Nesting and shadowing

When a local variable has the same name as a variable in an enclosing scope, it shadows the outer one. Code inside the block can’t see it any more—it is hidden in the “shadow” cast by the inner one—but it’s still there.

When we enter a new block scope, we need to preserve variables defined in outer scopes so they are still around when we exit the inner block.

- Define a fresh environment for each block containing only the variables defined in that scope.

- When we exit the block, we discard its environment and restore the previous one.

- Chain the environments together. Each environment has a reference to the environment of the immediately enclosing scope. When we look up a variable, we walk that chain from innermost out until we find the variable.

| |

# Blocks

# Syntax

A block is a series of statements or declarations surrounded by curly braces:

| |

It contains a list of statements.

| |

# Semantics

When we encounter a block statement, we create a new environment with the current environment and pass it into a function like this:

| |